1.29.2007

Tortoise: A Lazarus Taxon

Bob Burnett: Throughout their decade+ history, Tortoise have been a band that, regardless of style, sound, or the coming and/or going of a band member, have remained interesting, engaged and dynamic. They are an instrumental band in whom I hear many reminders of other music and moments in sound (Canterbury-style progressive rock, Neu! and Can krautrock, Koner electronica, Keith Levine/PIL guitarscapes, the Modern Jazz Quartet, the Joseph Holbrooke Trio’s inspired extrasensory freeform, Thomas Brinkman’s blips and rhythmic beats, Steve Reich’s phases, Edgard Varese’s organized sound, as well as quarters vibrating on top of the dryer, wind in the trees, growling howler monkeys in the rainforest…), but who all the while are a hugely influential group of players in their own right who have pushed music forward in unique and exciting new directions. Tortoise are perpetually involved with multiple music projects, be it playing in the studio with others, recording/producing other bands (for example, band member John McEntire's Soma Electronic Music Studios is one of Chicago’s finest), or in the studio themselves using their musical and engineering skills as added compositional tools. The results consistently result in rich instrumental timbre, delicate and intricate melodies and clear yet complex rhythms that make for rewarding and thoughtful listening.

Now comes along A Lazarus Taxon a comprehensive 3xCD, 1xDVD mini box set with a full 20 page booklet in English, German, Japanese and Spanish. The title "Lazarus Taxon" is perfect—it is a paleontological term for a species that disappears, then reappears in the fossil record. This collection includes rare singles from non-US releases and tour EPs, compilation tracks, previously unreleased material, and the nearly impossible-to-find out-of-print 1995 album Rhythms, Resolutions & Clusters. “Lazarus Taxon” also features a DVD compilation of most of Tortoise’s music videos and extensive and rare live performance footage. I was lucky enough to be one of the camera people on the song "Salt the Skies" which was originally featured on Brendan Canty and Christoph Green’s "Burn to Shine: Chicago" DVD release. Tortoise were the last of nine bands to play for that recording, and they simply blew me away with their skilled interplay.

Tortoise is also a group known for advancing the re-mix. Many of their own are featured on this compilation. I can remember a time when remix meant 12" dance singles, an extension on the original 3-minute song that usually brought repetitive rhythm track vamps for longer dance floor playing time. In Tortoise’s case it meant the opportunity for other producers to "go cubist" with their work, adding new dimensions and directions and making the work uniquely stand apart from the original conception. Included in this box are re-mixes of their own work as well as some interpretations they did of others' work—namely Yo La Tengo’s "Autumn Sweater," which in the hands of Tortoise becomes a slow, lovely sound sculpture.

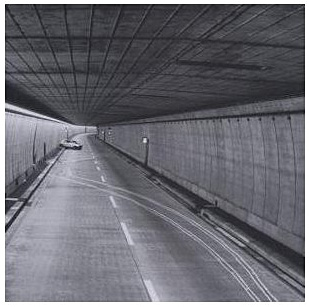

I must also note the black-and-white photography of car mishaps that appear as cover artwork in the box. It is the work of Arnold Odermatt, a retired Swiss police officer turned artist. Upon further research on the Thrill Jockey web page I discovered that as a policeman Odermatt was assigned to document auto accidents and police training. Odermatt’s photos were far more than snapshot-like documents and reflect nothing macabre or gruesome. He often photographed the accident scenes after all the officers had left and the clutter had been cleared revealing scratched, skid-marked roadways and marred tunnel walls. The photos are small, compact visual stories; you wonder what happened and why it happened, and are fascinated by the locations. His photos were uncovered by Berlin’s Springer and Winkler Gallery, which had Odermatt reprint them in limited editions. The photographs were an instant sensation and garnered Odermatt wide acclaim. The Springer and Winkler Gallery and Odermatt graciously allowed Tortoise to use photos for this package that they had selected.

Regardless if you have little or limited knowledge of Tortoise or if you already have a shelf of their releases, I highly suggest you look into this one. It is a value-priced box (under $20 US) that offers wonderful riches in return.

Mike Johnston: We need some sort of rosette, or star, or dancing pig, or something to indicate spectacular bargains and must-buys. This is just ridiculously cheap and is laden with treasurable things, plus it's an audiophile disc par excellence, that will sound fantastic on a good audio system. On a great-music-per-dollar/pound/euro scale it's almost as good as free.

Billie Holiday: All or Nothing at All

Mike Johnston: A very brief guide to buying Billie Holiday on record:

1933–1942 were the so-called "Columbia years," named after her main label during the period. These were the years in which she became famous as a pop chanteuse and was in full voice and flower. On disc, the period is extremely well-served by the currently going- but not gone-out-of-print Columbia "Quintessential" series, volumes 1–9, which contain all of the 153 songs she recorded for Columbia. This was the arc of her ascent, traditionally known as her "good stuff," that made her reputation and was once preferred by the public and record collectors. All nine volumes of the "Quinessential" series are delightful; none is particularly better than the others, and none are bad. Buy one or two, or a handful, or all of them.

In 1939, mainly because Columbia refused to record the harrowing "Strange Fruit," Billie freelanced for Milt Gabler at Commodore Records, mainly in two sessions, one in 1939 and one in 1944. Although not the best single-disk introduction to Holiday—it's a transitional period musically—the Commodore sessions

In 1939, mainly because Columbia refused to record the harrowing "Strange Fruit," Billie freelanced for Milt Gabler at Commodore Records, mainly in two sessions, one in 1939 and one in 1944. Although not the best single-disk introduction to Holiday—it's a transitional period musically—the Commodore sessionsIn 1942-44 she began using heroin and recording for Gabler at Decca. This was probably the happiest period of her professional life, because Decca treated her like the 1940s version of a superstar, getting the best songs for her to sing and pulling out the stops when it came to orchestral accompaniment. Holiday reveled in the treatment she received at Decca and the respect she was accorded. However, although well served on The Complete Decca Recordings

Although her Decca period didn't wind down until 1950, her career was permanently (and some think fatally) interrupted in 1947 when she was arrested and jailed for the better part of a year on drug charges. Worse, upon her release from prison she was permanently denied a cabaret card, meaning she could no longer perform in establishments that served alcohol—which of course meant most of them. Her drug use, legal problems, money woes, and personal problems escalated and intensified in the late '40s and throughout the '50s until her death, and she became a sort of postwar Michael Jackson, notorious with the public (and getting much more attention from the white press for her troubles than she ever got for her singing) as an aging former star providing a lurid spectacle as she went down in flames.

From a creative standpoint, the best was still yet to come, however. In 1952, Norman Granz signed her to Mercury, parent company of Verve. In the seven years before she died in 1959, she recorded nearly 100 songs for Verve, now known as her late or Verve period. The standard line is that this period is a triumph of experience, judgment, and musical intelligence over declining vocal ability, but the fact is that her work during this time was very uneven. A good number are excruciatingly awful ("unlistenable recordings made when she could barely find the energy to enunciate or keep in tune," writes Gary Giddins). But the best of Billie Holiday's Verve recordings are one of the glories of recorded music. In recent years the reputation of her Columbia period and her Verve period have flip-flopped; most Billie Holiday lovers now admire and prefer the later period over the earlier.

And most, although not all, of the best songs from this period are present on this indispensable Verve compilation, All or Nothing at All. It comprises all of Songs for Distingué Lovers and Body and Soul, plus six or seven more high points plucked from other records of the period. In toto it's a great work of art and both a pleasurable and a moving listening experience, whether dipped into, selected and excerpted, or listened to straight through.

Also, importantly, for me at least, it contains none of the songs from Lady in Satin. The controversial Lady in Satin is really a case study in misguided pop cultural assumptions, and encapsulates down into the present day the misunderstanding that always existed between Billie Holiday and the broader American public. Very unfortunately, Lady in Satin has gotten the reputation as her "best" record, for two reasons. First, Billie herself said at the end of her life that it was her favorite. But to interpret this, you need to consider the context—Billie always considered recording with a full string band to be a mark of respect to her, and the treatment she got while making this record at the very end of her short life must have felt like a return to the treatment she got during her Decca years—it was her last star turn. And second, it's beloved of myopic "audiophiles" as the best sounding Billie Holiday record, due only of the recording of the strings, ignoring her voice, which to me makes about as much aesthetic sense as ranking 9/11 videos for artistic quality—i.e., no sense at all. For this reason, Lady in Satin is often purchased by neophytes as "the best," and their one and only representative Billie Holiday record.

This is just so tragically wrong. Her voice on this record is ragged and hoarse, her range—always limited—even more truncated, making the contrast with the Nelson-Riddlesque Ray Ellis string arrangements almost bizarre in its cognitive dissonance. Personally, I have no objection to the completist owning this record, and no quarrel with the Lady Day aficionado who finds great pathos and meaning in her performances here, as many do. But the ruin of her once sweetly expressive voice is shocking, and as a listening experience the record is a travesty because of the hokey, sappy, horrible strings-all-over-the-place Lawrence Welk soundscape. However jazz fans might feel about it, it should not be anybody's only Billie Holiday record. I don't even own it.

If you love Billie Holiday, or jazz—or, hell, music—make sure all your friends buy All or Nothing at All as their one-and-only Billie Holiday record, and make sure they don't think that having Lady in Satin as their sample disk means that they've got any idea at all what Billie Holiday is all about. It sticks out as the biggest anomaly in her entire extensive catalog.

To round out a great Billie Holiday collection on record, the other essential from the Verve years is the great Lady Sings the Blues, a perfect record and one of the high points of music on record for me. Unfortunately, you can't really buy this on CD right now, because the only available CD versions add songs that weren't on the original album, omit some that were, and change the order of the rest. This is unnecessary vandalism, and you should hold out until you can get the record in its original state. And that is:

Side A

Lady Sings the Blues

Trav'lin' Light

I Must Have That Man

Some Other Spring

Strange Fruit [1956 version]

No Good Man

Side B

God Bless the Child

Good Morning Heartache

Love Me Or Leave Me

Too Marvelous for Words

Willow Weep for Me

I Thought About You

With Wynton Kelly on piano, Kenny Burrell on guitar, Aaron Bell on bass, Leonard Browne on drums, Charlie Shavers on trumpet, Paul Quinchette on tenor sax, and Anthony Sciacca on clarinet on the first eight songs, and Bobby Tucker on piano, Barney Kessel on guitar, Red Callender on bass, Chico Hamilton on drums, Willie Smith on alto saxaphone, and Sweets Edison on trumpet on the last four. Having Lady Sings the Blues and All or Nothing at All is a way to neatly possess almost all of the very best, and none of the worst, of late-period Billie Holiday, who was only 44 years old when she left this earth but had lived a very full life as an artist.

1.27.2007

Trentemoller: The Last Resort

Kim Kirkpatrick: Anders Trentemoller's The Last Resort is quite a musical blend of contemporary genre, with programmed techno, ambient and minimal electronics, and scratchin’, all blended together with some fine guitar and heavy bass playing throughout. The Last Resort touches on many a predecessor’s sound and beats, going back to Tangerine Dream, early Human League, New Order, and Tricky (to name a few), right up to the latest from the Kompakt label. For an hour and twenty minutes each track flows into the next smoothly, and the direction changes frequently, but Trentemoller guides the transitions with intelligence and creativity.

The Last Resort spends much of the time in an atmospheric, down tempo mode but genres are always being changed, the coloring and mood is ever shifting and swirling until you really have no idea what track you are hearing, or even how long the CD has been playing. On "The Very Last Resort" Trentemoller comes into the track ambient, hissing, dreamlike, with backwards and acoustic Spanish-flavored guitar. This gives way to waves of echoes, cymbals, and a tremolo Spaghetti Western electric guitar. The track slowly, naturally fades out with organ and some subtle channel shifting. The other twelve tracks are just as flowing a mix as the one described above; any of them can drift by or hold your attention completely—it's up to you and your mood at the time.

I think you need this CD if you want to be up to date with current music. It stands out as masterful, complex, and infinitely listenable. As I mentioned above, it takes over your listening experience; you get lost in it, lose your sense of time—an effect I always enjoy from some music. Search out the initial release if possible—it has an extra disc of remixes and singles. The bonus material will give you some background on Trentemoller’s work.

1.26.2007

Fennesz: Endless Summer

Bob Burnett: I probably have a Fred Frith record from 30+ years ago to thank for my appreciation of Christian Fennesz today. After all, Frith was one of the players who helped me make sense of this thing called music. His album Guitar Solos

So now, Christian Fennesz' work takes guitar into another possible direction by bringing laptop sound composition into the mix to create warmth, energy, sound collage, abstraction, clarity and new sounds. While much of the music is somewhat abstract and not built around typical song structure, there isn’t anything distant, sterile or bizarrely complicated about what he does. At times the electronics seem to take over in a floating, repeating-pattern wash; you feel that he, like the listener, is just stepping back and listening to what he’s so effectively put in motion. Other moments feature slow guitar strumming that's filtered and affected by any number of applications, laptop enhancements and feedback-like pop/click textures. I appreciate his work because he re-thinks the possibility for guitar and follows a path of intricate design for the instrument. Sometimes when playing Fennesz I also harken back to the newness and joy I felt upon first hearing the collaborations of Brian Eno and Robert Fripp back in the mid '70s. Other moments connect me with the freshness and revitalization Kevin Shield's guitar-based sound forms My Bloody Valentine offered.

Fennesz’ album “Endless Summer” is a re-issue of an album he made in 2001. This time around the release features a few more tracks. Be it 2001 or 2007 the album sounds very much of today. I suppose one of the arguments for a re-release is that it hopefully will garner more attention and thereby be heard by more people. I can only hope the same thing happens for another wonderful album of his, Venice, which unfortunately seems to be either very expensive or out-of-print. Strange, considering that it, like Endless Summer, was a critical darling and was featured very highly on progressive music "best of" listings a few years back. Another album that I’ve listened to extensively that involves him is David Sylvian’s outstanding Blemish.

All told Fennesz is on my "need to hear whatever comes out" list. His work thoroughly fascinates me.

1.25.2007

Somei Satoh: Litania—Margaret Leng Tan Plays Somei Satoh

Bob Burnett: I was drawn to this album for a few reasons. The primary reason was that it is an album that features pianist Margaret Leng Tan, a player whose interpretations of John Cage represent some of my favorite interpretations of one of my favorite composer's work—for piano as well as the simple yet delightful toy piano. She has become known as "the leading exponent of Cage today" according to The New Republic. In addition to being known for her playing of Cage, she was the first woman to graduate from the Julliard School of Music with a Doctorate of Music degree from the University. Along on this recording are Lise Messier, soprano; Frank Almond, violin; and Michael Pugliese, percussion.

I was not familiar with composer Somei Satoh or "Litania" before hearing this recording. "Litania" is the first in a series of compositions Satoh did for piano, all of which explore the reverberative qualities of the instrument through tremolo technique. The drones create subtle time lags through a digital delay process. This creates a rich harmonic texture, which is further intensified by the overlaying of a second or third piano. Upon listening to "Litania" as well as the other compositions on this album I felt immediately drawn to LaMonte Young’s sadly out-of-print masterwork "The Well-Tuned Piano"; which is a perfect bringing-together of small, elegant moments of peaceful minimalism in conjunction with large, full, clouds of dense building clusters. Similarly, it seems Satoh’s thinking is in the same place as Young (and John Cage for that matter) when asked about his process for creating "Litania":

I think silence and the prolongation of sound is the same thing in terms of space. The only difference is that there is either the presence or absence of sound. More important is whether the space is "living" or not.

Also—while sitting here listening to the conclusion of "Litania" with the CD loaded into iTunes (on shuffle play) the song that popped up afterwards was "European Son" by The Velvet Underground and Nico. The transition was uncanny.

This is not an easy listening classical music experience. However, it’s also not a random sounds-style contemporary free-for-all. There is a lot to be experienced within its complexity and energy as well as the ebb and flow that are vital to the overall composition. Plus, I can’t speak highly enough about being able to listen to anything Margaret Leng Tan touches.

This is not an easy listening classical music experience. However, it’s also not a random sounds-style contemporary free-for-all. There is a lot to be experienced within its complexity and energy as well as the ebb and flow that are vital to the overall composition. Plus, I can’t speak highly enough about being able to listen to anything Margaret Leng Tan touches.

Hammer of God: Bach Harpsichord Concerto in D Minor, BWV 1052

Mike Johnston: There are some jazz albums that every non-jazz-lover feels he must own, Kind of Blue foremost among them. Likewise, there are some classical pieces so great that everybody should own them, regardless of whether they normally like classical music or not. In the '40s and '50s every self-respecting music lover owned a copy of Beethoven's 5th (typically Toscannini's); later, when Mozart had superceded Beethoven as the classical master of popular choice, every record collection had to have A Little Night Music (Eine kleine Nachtmusik) and of course Vivaldi's Four Seasons. But foremost among such pieces for me is Bach's marvelous D-minor 1052.

Robert Plant once used the phrase "hammer of the gods" when talking about what he intended to deliver on a then-upcoming new Led Zeppelin album, and the phrase stuck to describe the band's sound. But back in a time when the idea of God had real tooth, Johann Sebastian Bach was a man who believed the purpose of his entire existence was to exalt the greater glory of God. Possibly the greatest musical genius in history, he was the real deal, the hammer of God—the phrase describes the stormy and glorious drama of his best music to a T.

And it describes nothing so well as the 1052. Nominally a harpsichord concerto—a piece for harpsichord accompanied by orchestra—it was often played on piano in the "modern" era, prior to the "original instruments" revival of the 1970s and 1980s. It has three parts, or movements, in the typical Baroque pattern of fast-slow-fast. In this music, you want the harpsichord—the orchestra and the distant miking take the ridiculous bite off the sound that sometimes ruins close-miked harpsichord recordings, and there's just no way that the piano can convey the high, thin, unmodulated, almost hillbilly high-mountain sound the drama of the piece demands.

There are plenty of indifferent versions of this piece out there, so you have to pick carefully. Still the best 1052 overall, in my opinion, is Trevor Pinnock's. Pinnock was an enfant terrible of the original instruments craze, a keyboardist who devoted himself to harpsichord when it had been relegated to historical and academic recordings. As the bandleader of a young group called The English Concert (he directed these performances from the keyboard), he wore his hair long in those days and sometimes talked, in interviews, about bringing the beat and exuberance of rock 'n' roll to Baroque music. His fierce Goldberg Variations competed with Glenn Gould's evergreen piano version in the 1980s (Pinnock seems to me more influenced by Gould than I ever heard him admit), and The English Concert's Brandenburg Concertos were a bestseller (along with their Four Seasons, which sold like a pop hit and made Pinnock a classical superstar). His 1052 was every bit as good as these, if not better—an absolute high point of his early career. Its fierce, driving beat is balanced by nuance and a great feel for the logic of the piece, combining for a peerlessly dramatic reading. Hammer of the gods indeed. It's now available on a 5-CD set of all the concertos on Deutsche Grammophon's Archiv label. While there's nothing wrong with any of this music or any of these performances, five CDs of accompanied instrumental music by Bach may be a little bit much of a commitment for the non-classical listener.

An even better bet for casual listeners is a newer (Y2K) record by an outfit that is fast becoming one of my favorite classical bands, the Cologne Chamber Orchestra under Helmut Müller-Bruhl. Here you get four complete Bach harpsichord concertos (No. 1 in D minor, BWV 1052; No. 2. in E major, BWV 1053; No. 4 in A major, BWV 1055; and No. 5 in F minor, BWV 1056) for a mere nine bucks—that's $2.25 per concerto, and it's hard to do better than that, value-wise. But the best part is that the music-making is so good. This is one of the few 1052's that can compete with Pinnock's. Müller-Bruhl seems to have a knack for finding just the right tempo and phrasing to make music sound natural and right, never plodding or leaden, never rushed or glossed-over, and his 1052 nearly equals Pinnock's for drama—not an easy thing to pull off. And it is even better recorded: the orchestral parts have a detailed fullness and an immediacy that you hear in only the best classical recordings. It sets off the ethereal wash of the harpsichord superbly. This is really an enjoyable record sonically as well as musically.

And no record collection should be without a great Bach 1052.

Robert Plant once used the phrase "hammer of the gods" when talking about what he intended to deliver on a then-upcoming new Led Zeppelin album, and the phrase stuck to describe the band's sound. But back in a time when the idea of God had real tooth, Johann Sebastian Bach was a man who believed the purpose of his entire existence was to exalt the greater glory of God. Possibly the greatest musical genius in history, he was the real deal, the hammer of God—the phrase describes the stormy and glorious drama of his best music to a T.

And it describes nothing so well as the 1052. Nominally a harpsichord concerto—a piece for harpsichord accompanied by orchestra—it was often played on piano in the "modern" era, prior to the "original instruments" revival of the 1970s and 1980s. It has three parts, or movements, in the typical Baroque pattern of fast-slow-fast. In this music, you want the harpsichord—the orchestra and the distant miking take the ridiculous bite off the sound that sometimes ruins close-miked harpsichord recordings, and there's just no way that the piano can convey the high, thin, unmodulated, almost hillbilly high-mountain sound the drama of the piece demands.

There are plenty of indifferent versions of this piece out there, so you have to pick carefully. Still the best 1052 overall, in my opinion, is Trevor Pinnock's. Pinnock was an enfant terrible of the original instruments craze, a keyboardist who devoted himself to harpsichord when it had been relegated to historical and academic recordings. As the bandleader of a young group called The English Concert (he directed these performances from the keyboard), he wore his hair long in those days and sometimes talked, in interviews, about bringing the beat and exuberance of rock 'n' roll to Baroque music. His fierce Goldberg Variations competed with Glenn Gould's evergreen piano version in the 1980s (Pinnock seems to me more influenced by Gould than I ever heard him admit), and The English Concert's Brandenburg Concertos were a bestseller (along with their Four Seasons, which sold like a pop hit and made Pinnock a classical superstar). His 1052 was every bit as good as these, if not better—an absolute high point of his early career. Its fierce, driving beat is balanced by nuance and a great feel for the logic of the piece, combining for a peerlessly dramatic reading. Hammer of the gods indeed. It's now available on a 5-CD set of all the concertos on Deutsche Grammophon's Archiv label. While there's nothing wrong with any of this music or any of these performances, five CDs of accompanied instrumental music by Bach may be a little bit much of a commitment for the non-classical listener.

An even better bet for casual listeners is a newer (Y2K) record by an outfit that is fast becoming one of my favorite classical bands, the Cologne Chamber Orchestra under Helmut Müller-Bruhl. Here you get four complete Bach harpsichord concertos (No. 1 in D minor, BWV 1052; No. 2. in E major, BWV 1053; No. 4 in A major, BWV 1055; and No. 5 in F minor, BWV 1056) for a mere nine bucks—that's $2.25 per concerto, and it's hard to do better than that, value-wise. But the best part is that the music-making is so good. This is one of the few 1052's that can compete with Pinnock's. Müller-Bruhl seems to have a knack for finding just the right tempo and phrasing to make music sound natural and right, never plodding or leaden, never rushed or glossed-over, and his 1052 nearly equals Pinnock's for drama—not an easy thing to pull off. And it is even better recorded: the orchestral parts have a detailed fullness and an immediacy that you hear in only the best classical recordings. It sets off the ethereal wash of the harpsichord superbly. This is really an enjoyable record sonically as well as musically.

And no record collection should be without a great Bach 1052.

1.24.2007

Terje Rypdal: Vossabrygg

Bob Burnett: I’ve been on a Terje Rypdal sabbatical for several decades. Not that he did anything particularly wrong—I used to love his fuzzy, thunderous, distant guitar sounds and played his records all the time. Terje Rypdal was one of those guys who would light up the radio station phone lines with callers asking "what are you playing?" when I'd play him on my late night show. ("Terje Rypdal—right—Rypdal, yeah, he's Norwegian….R-Y-P-D-A-L" went the conversation….) 1979’s Descendre, being floating nighttime sound at its best, made me spell his name for curious listeners too as did other albums from that era such as Waves (1973), Odyssey (1975), and After the Rain (1976). I also found a lot to like about 1978’s inspired trio work with Jack DeJohnette and Miroslav Vitous as well as his incredible playing on Michael Mantler’s Edward Gorey-inspired tales, The Hapless Child.

Somehow, I just stopped buying his albums, moved on to other things; probably felt like I needed to expand beyond the ECM Records artists and that lustery sheen of producer Manfred Eicher's sound.

That’s all changed with Vossabrygg. I’m back. And I’m really enjoying the reunion.

Vossabrygg is Norwegian Rypdal’s tribute to circa 1970-era Miles Davis, specifically Bitches Brew as well as the 1969 pre-Brew classic In A Silent Way. From the first notes of Rypdal’s lead-off "Ghostdancing"—which quotes directly from the theme of the Bitches Brew composition "Pharoah’s Dance," it becomes quickly obvious that this is a serious, thoughtful, and reverant effort.

As was the case with Miles Davis' genius-composing "Directions in Sound by Miles Davis" as it says on the Columbia albums circa 1968–74, Rypdal loads up the layers of playing and players —two keyboardists (Bugge Wesseltoft, electric piano, synthesizer; Stale Storløkken, Hammond organ, electric piano, synthesizer) and two percussionists (Jon Christensen, drums; Paolo Vinaccia, percussion). Rypdal’s John McLaughlin-like fuzz tone on "Ghostdancing" and trumpeter Palle Mikkelborg’s muted trumpet work create further connection to the rich Miles Davis sound. In addition, bassist Bjørn Kjellemyr adds great pulses and structure, and Marius Rypdal, Terje's son, contributes masterfully and cohesively with electronic blips, percussive turntable scratches, and a variety of sound samples.

Despite all this referencing to Miles Davis, this is by all means a Rypdal record. His fuzzy, far-reaching "Nordic Cool Jazz" sound has defined Rypdal’s playing since he first gained notice in the late '60s playing fractured, burning Sonny Sharrock-style guitar in Lydian Chromatic Concept inventor (and noted Miles Davis influence during his modal composition breakthrough Kind of Blue) George Russell’s ensemble along with eventual ECM Records mate saxophonist Jan Garbarek.

Thank goodness Terje Rypdal didn't pay attention to what was said about this era of Miles Davis' work in the documentary "Ken Burns Jazz," in which Gerald Early put down Bitches Brew by likening it to "playing tennis without a net." I think Miles Davis would have loved this album and not just because it harkens back to some of his own strongest work, but because it shows the ever-expanding artistry still within Rypdal; a player who has been around for forty-plus years and is still reinventing himself, still hearing new possibilities, still exploring—something Miles Davis did too throughout a long career in "directions" in music.

So for me it’s a welcome return to Terje Rypdal’s music. In Vossabrygg he’s created a fine listening experience.

1.22.2007

Koshari: Unless

You need a few friends you can trust, ones who have heard as much music as you. If you are really fortunate, they do not have the exact same taste as you. I have friends (some I have never met in person) that have expanded my musical enjoyment, my education, greatly. It could be jazz, rap, reggae, blues, country, metal; I'm talking boatloads of music I would never have found or heard otherwise. These people shared their knowledge, filtered out the crap, and fed me the best from various genres.

My other tip for staying engaged with the music around you is to give it your time. Honestly, the older I get the more likely I am to turn against some band immediately: “heard this before,” “sounds just like…,” etc.* But if certain friends turn me on to some music, I respect their opinion enough to give it an honest chance. And being an artist, and having tried to be a musician, I also think everyone needs to remember these musical efforts are someone’s life work, it is what they live for. So it deserves some effort on your part, and for me that means repeated listening. I may hate a CD because of my mood—it is very possible I am grumpy and feeling like not liking anything. I frequently find it requires time for a lot of music to sink into my aging brain. I might listen to a CD over a few days, or on repeat while working. Playing it through three or four times can change my opinion. That said, I still hear plenty of music I just hate, and know I always will. But it is far more common for me to have questions (about the music or myself) after the first time through, and that encourages me to give it another try.

• • •

All of the above applied to my hearing Koshari’s Unless (2005), I could easily have dismissed it, aged a bit more, and moved on in a huff! But because a longtime friend (and fellow guitar player) had praised them, and because the guitarist in the band was so warm, sincere, and friendly when we first met (he gave me a copy), I knew I should give it more time. I also knew the following applied; some music has to be played loud or you might as well turn it off. Koshari** is just such a band. With the volume down low you can dismiss it as lightweight, derivative of Swervedriver, My Bloody Valentine, Lush—just another band. Turn them up, way up, give them a few listens back to back, and the music will open up and breath for you. Sure, Barbara Western’s vocals are breathy, with a familiar ethereal quality at times, but they are strong too, and with subtle expression. Bryan Baxter’s guitar is full of recognizable tones but he makes them his own, and his diverse effects serve each song specifically. Danny Ralston’s drumming is superb, intelligent, and creative enough that I have gone through the whole CD focused on just his playing.

All of the above applied to my hearing Koshari’s Unless (2005), I could easily have dismissed it, aged a bit more, and moved on in a huff! But because a longtime friend (and fellow guitar player) had praised them, and because the guitarist in the band was so warm, sincere, and friendly when we first met (he gave me a copy), I knew I should give it more time. I also knew the following applied; some music has to be played loud or you might as well turn it off. Koshari** is just such a band. With the volume down low you can dismiss it as lightweight, derivative of Swervedriver, My Bloody Valentine, Lush—just another band. Turn them up, way up, give them a few listens back to back, and the music will open up and breath for you. Sure, Barbara Western’s vocals are breathy, with a familiar ethereal quality at times, but they are strong too, and with subtle expression. Bryan Baxter’s guitar is full of recognizable tones but he makes them his own, and his diverse effects serve each song specifically. Danny Ralston’s drumming is superb, intelligent, and creative enough that I have gone through the whole CD focused on just his playing. Koshari’s Unless is packed with atmosphere, beauty, substance, and it rocks. It is progressive, ambient, hard core, surf, metal—alternate tuning, droning, chiming, shimmering rock music. With volume and repeated listening the subtle, detailed production quality opens up for you. The recording has a clarity and space to it, and the band's performance is connected, displaying an honest interaction and awareness of each other.

Koshari’s Unless is packed with atmosphere, beauty, substance, and it rocks. It is progressive, ambient, hard core, surf, metal—alternate tuning, droning, chiming, shimmering rock music. With volume and repeated listening the subtle, detailed production quality opens up for you. The recording has a clarity and space to it, and the band's performance is connected, displaying an honest interaction and awareness of each other.And it rocks!

*Years ago, a friend gave me grief about playing the first R.E.M. record (then brand new) on the radio. His position was they were so derivative it was criminal, and I had no business playing them. He told me, “If I want to hear The Byrds, I’ll play The Byrds!"

**The Hopi Kosharis are considered to be Clown Kachinas. They behave in the manner of Pueblo clowns, engaging in loud conversation, inappropriate actions and of course, gluttony. They are often drummers for the dances. Kosharis are figures that are both sacred and profane. They are the ultimate example of overdoing everything they set out to do.

Guster: Ganging Up on the Sun

Bob Burnett: OK. I’m treading into an area that is a critical challenge. I’m writing about a group I know little about beyond a few basic things. Also, being traditionally known to my c60 pals for gravitating towards being the voice for freeform “here I stand, jacket over my shoulders, holding a Galois, wishing my hair looked liked Bernard-Henry Levy” intelligensia music guy, I’m attempting to log in on a pretty straight-ahead, somewhat popular group.

A friend of mine told me about Guster. He’s a professional musician and began his tale of Guster this way: “My 17-year-old daughter was listening to it…and usually I’m like, you know…ehhh...when she’s playing things. Well…my ears turned to Guster and said—wait a minute….these guys are good.” I also mentioned to a 25-year-old work colleague that I had been “listening to an album by some band that started in the Boston area….starts with a G…I dunno…pretty good.” She, being from nearby New Hampshire, immediately, enthusiastically shouted in her New England Fenwayese, “GUSTA! Yer listenin’ to GUSTA!—I LOVE GUSTA! Been listenin' to 'em since high school!”

So there you have it. Two positive set-ups. To me the “big” songs are at times too big, the quiet songs too falsetto and somewhat cute, the guitars kind of crashy, but they are really good at being a big-crashy-at-times-falsetto band. I completely see being a long time devotee to them. In times when many "pop" albums sound assembled, this one sounds played. It was recorded in Nashville, features a diversity of instruments including lap steel guitar, banjo, dulcimer and trumpet. The lead-off song, “Lightning Rod,” really is what makes you tap into what's going on. It's a lovely, well put together song. It must have been the one to turn my guitar-playing friend’s head towards his daughter’s room and say, "hey...this isn’t Fergie…."

1.17.2007

Pauline Oliveros, Stuart Dempster, Panaiotis: Deep Listening

Bob Burnett: On Deep Listening, The Deep Listening Band (known then as trombonist Stuart Dempster and accordionist Pauline Oliveros, along with voice and sonic cohort Panaiotis) recorded within the extraordinary acoustics of the Fort Worden Cistern in Port Townsend, Washington, a cavernous underground water tank that has a natural 45-second acoustic reverberation time. The band climbed down a ladder into the cistern, instruments in tow (in addition to the accordion and trombone, didgeridoo, conch shell, garden hose, and metal fragments) and produced four compositions of lasting fascination.

The Deep Listening Band’s long-working relationship has made them masters of overlapping, elongated reverberating sound compositions. In this case, the ability to tap into the magical possibility within the cistern only advanced their ability to create meditative interplay. This album consists of four distinct environments ranging in duration from ten minutes to twenty-five minutes.

Pauline Oliveros has been working in music and sound since the early 1960s. She has created in several disciplines including early works in electronics/tape (“Alien Bog” for example) but to me, her strongest and most identifiable work falls within the Deep Listening Band context. The term "Deep Listening" is a patented trademark of the Pauline Oliveros Foundation, Inc. "For me, Deep Listening is a lifetime practice,” she says. “The more I listen, the more I learn to listen. Deep Listening involves going below the surface of what is heard and also expanding to the whole field of sound whatever one's usual focus might be. Such forms of listening are essential to the process of unlocking layer after layer of imagination, meaning, and memory down to the cellular level of human experience."

Pauline Oliveros has been working in music and sound since the early 1960s. She has created in several disciplines including early works in electronics/tape (“Alien Bog” for example) but to me, her strongest and most identifiable work falls within the Deep Listening Band context. The term "Deep Listening" is a patented trademark of the Pauline Oliveros Foundation, Inc. "For me, Deep Listening is a lifetime practice,” she says. “The more I listen, the more I learn to listen. Deep Listening involves going below the surface of what is heard and also expanding to the whole field of sound whatever one's usual focus might be. Such forms of listening are essential to the process of unlocking layer after layer of imagination, meaning, and memory down to the cellular level of human experience."If you are further intrigued by the concept of natural reverberation as part of music I also suggest Alder Brook

The Deep Listening album was originally released in 1989 and has been hugely influential to others who create music that brings into account acoustic environment as a crucial element in the understanding of sound. As I listener I find great benefit from the slowly evolving, beautiful sound created by the group.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)